Subscribe for our newsletter to have the latest stories and curated art recommendations delivered straight to your inbox

LATEST ARTICLES

INTERVIEWS

Get to know Dean O’Callaghan

Dean O’Callaghan is an Australian artist and educator. After decades of juggling between the two careers, he is now a full-time artist. His very well defined minimalist geometric abstract style has brought him a well-deserved recognition. His art has been part of numerous exhibits in Australia and are now part of private collections. Get to know Dean and find out what are his current projects and plans. 1. Where do you live? I live and work from my studio in Moora, a rural Western Australian town around 187km north of the city of Perth. 2. Tell us a bit about you and your artistic career? I Studied Fine Arts and I took an Education Degree course at Curtin University of Technology and graduated with a Bachelor of Education with distinction in 1990. In 1983, I became a member of the Western Australian Contemporary Art Society and from 1987 to 1988, was elected president of the Society. During this time, I participated in many mixed exhibitions at various galleries in Perth and Fremantle. I have held three pivotal solo exhibitions in 1995, 99 and 2019. I lectured part time in visual arts in Technical and Further Education Colleges in Western Australia. Art by Georgia O’Keeffe,Alexander Rodchenko and Patrick Wilson 3. What are the biggest sources of your inspiration? I’m inspired by modern and contemporary architecture found in New York, Singapore, Melbourne, and Perth. I love Georgia O’Keeffe’s cityscapes paintings, the New York-based artist Gary Petersen and I follow Californian artist Patrick Wilson. I admire the work of Russian artists and photographers such as El Lissitzky, Alexander Rodchenko and Arkady Sjaichet. Another constant source of inspiration are the rural landscapes of Western Australia. 4. Is there a single work, a project that is pivotal in your career? Solo exhibition in 2019 was a pivotal moment in the development of my minimalist style. 5. Could you please describe your creative process? I like to work through a process of exploring ideas using digital drawing tools. From there I transfer my design to canvas using a grid method. I mask up the canvas and apply an underpainting for each hue using a brush and follow up with final applications of color using either spray or brush techniques. By using this underpainting and spray technique, I feel that I have the option to allow subtle color variations to come through. It also provides a strong base for any final spray application. Once I have my areas of color completed, I apply line work which provides another dimension to my work. 6. What is behind the pictorial language of geometric abstraction? With my work based on architectural forms, I was looking to simplify, and to minimize the forms down to their basic shapes. Building facades, windows etc. were all treated in flat areas of colors and I became particularly interested in the Deconstructive architecture style developed in the 1980’s. With the work I produced based on rural landscapes, the geometric shapes and color were directly influenced by the shapes of fields, the color of various crops over a growing season, and road networks crisscrossing the landscape. From the beginning of 2021, I decided to take out diagonal lines and shapes and use only vertical and horizontal lines and shapes. I felt a sense of calm contemplation coming through my paintings and I became interested in using tonal variations and lines to create depth within my paintings. Enter Stage Left, 2021, Acrylic on canvas Summer Nights, 2021, Acrylic on canvas 7. In addition to being an artist you are an art educator, what advice would you give to a young artist? Having lectured in visual arts for many years, my advice to young artists is to be true to yourself. Although it is important to take influences from other artists, contemporary as well as historically, always aim to explore ways you can bring this into your own experiences and cultural heritage. Contemporary art is not about a style. It is more about what the concept is and how you use techniques and media to communicate your concept. 8. What are you working on right now? I continue to work on my paintings based on abstract minimalist forms. While I have been fortunate to have work shown on platforms such as RtistiQ, I am looking forward to an opportunity to exhibit my work in either a Singapore or European art gallery in 2022-23. 9. How did the pandemic affect your creative process? I am very fortunate to be living and working in Western Australia which has been on the most part, free from Covid 19 lockdowns. Recently my paintings have developed a Covid 19 theme but mostly, my creativity continues as normal. However, travelling internationally or indeed within Australia has led to a couple of cancelations to prominent art fairs. Arrival, 2020, Acrylic on canvas Outward Bound, 2020, Acrylic on canvas 10. Any thoughts on social media and art? Social media has provided an excellent way to get feedback from people from around the world. It’s also a way to get noticed and develop networking opportunities with galleries and art fair directors. 11. What else should we know about you? I have undertaken collaborative work with the Moora Indigenous community with the most recent being a mural at the town speedway. Learn more about the project here. Discover more art by Dean O’Callaghan by checking his profile on RtistiQ.

ARTIST SPOTLIGHT

5 Famous Artists Exploring Geometric Abstraction

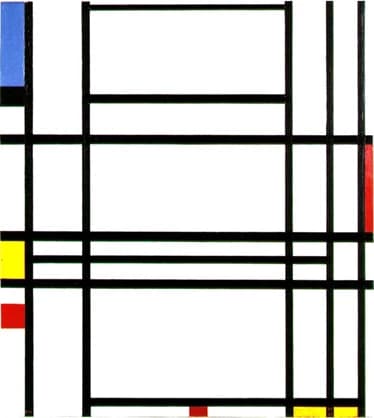

Geometry is, to some degree, the basis of all painting. Artists use the basic shapes to construct a different world. By combining them in ever more elaborate ways, incredibly complex images can arise. That’s the way that geometry was used in art for thousands of years. But as modern art began to emerge, artists started using basic geometry in an abstract way. Thus the term Geometric Abstraction was developed. Rather than making art that represented real life with these fundamental shapes, artists went directly to the shapes themselves. What they found as they began doing this was a rich, mostly untold history of geometric abstraction. Cultures native to the American Southwest had been employing this style going back countless generations. Muslim cultures, given Islam’s ban on representative images, had their own tradition. And the list goes on, including yantra designs in India and Aboriginal art in Australia. Drawing from these traditions and striking out paths on their own, many artists began exploring abstract geometric art, and the results speak for themselves. Geometry art, with its emphasis on geometric shapes in art, opens up new dimensions of artistic expression. From intricate patterns to minimalist designs, artists explore the inherent beauty of geometric shapes and their interconnections. By manipulating lines, angles, and forms, geometric art stimulates visual perception and invites contemplation. Let’s look through the five of the most famous artists in the field. Piet Mondrian Composition No. 10 (1942) by Piet Mondrian Piet Mondrian (1872 to 1944) was born in the Netherlands. But his career went far afield of his homeland. Over his lifetime, he helped create abstract art. His work gradually moved from the representational to the purely abstract, giving us a clear view into the development of his thinking and style. His most popular geometric abstract art paintings contain large amounts of white space, intersected by straight lines, with some fields of primary color. That style became synonymous not only with the artist but with the growing field of modern art itself. These paintings are sophisticated, direct, and show a radical break with Western art. They remain some of the most iconic paintings of the 20th — or any — century. Wassily Kandinsky Squares with Concentric Circles (1913) by Wassily Kandinsky Like Piet Mondrian, Wassily Kandinsky (1866 to 1944) helped invent abstract art as we know it today. And like his contemporary, his career began as a representational artist — though he continued to push the boundaries until finally taking the leap into pure abstraction. Kandinsky’s influence is felt both from the art he created and for the theoretical works that he wrote. He helped clarify our thinking on just what geometric abstraction art is and how it works, as well as answer why we should paint in this style at all. Music had a major effect on him. Since it is purely abstract, he borrowed terms from music to describe his work and painting in general. He also imbued his art with profound spiritual feeling. Sonia Delaunay Rhythme (1938) by Sonia Delaunay Sonia Delaunay (1885 to 1979) was a force to be reckoned with. She co-founded Orphism — an art movement that combined the exuberant color of Fauvism with the visual abstraction of Cubism, all while pushing both into new frontiers past any representation. Her work is also notable for its scope. She was a painter first, but took the ideas she discovered in her studio and applied them to a wide range of practical items, like clothing and furniture. She even famously decorated a Mantra M530A sports car. Today, Delaunay’s paintings are considered high level classics in the field of geometric abstraction. Barnett Newman Onement 1 (1948) by Barnett Newman Barnett Newman (1905 to 1970) is one of the most controversial artists of the 20th century. Not because of the content of his paintings, but because of how confrontationally content-less his paintings were. He started developing surrealism paintings before landing on his devastatingly simple style. His canvases often contain just two colors, with one large field interrupted by a single stripe (consider Onement 1 pictured above). His work Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow and Blue III was famously attacked by Gerard Jan van Bladeren, who stabbed it with a knife in 1986. After its $400,000 restoration, van Bladeren returned in 1997 to stab it again. He couldn’t find the painting, so he chose to deface Newman’s Cathedra instead. Kazimir Malevich Suprematism (1915) by Kazimir Malevich Kazimir Malevich (1879 to 1935) was a Russian artist whose career was not entirely in abstract art, though he gave us some of the most striking pieces in the field. He founded the school of Suprematism with his 1915 manifesto on the subject. His new art movement was based on simple shapes painted in few colors. This laid the groundwork for geometric abstraction. His suprematist paintings are daring in their simplicity, dramatic in their composition. This work goes to show that using the barest of essential elements, an artist can still make us think and, most importantly, feel. Conclusion Abstract art has captivated the world with its unconventional beauty and the boundless creativity it offers. Over the years, numerous abstract artists have risen to fame, leaving an indelible mark on the art world. Their famous abstract artwork continues to inspire and challenge perceptions of what art can be. One prominent aspect of abstract art is the incorporation of geometric elements. Geometric abstract art explores the use of precise shapes, lines, and compositions to convey emotions and ideas. The interplay of geometric forms creates a visually captivating experience, showcasing the artist's mastery of balance, symmetry, and spatial relationships. Famous abstract artists such as Wassily Kandinsky, Piet Mondrian, and Kazimir Malevich are celebrated for their contributions to geometric abstraction. Their bold geometric paintings and compositions have become iconic representations of the movement, pushing boundaries and defying traditional artistic norms. Passionate about Geometric Abstraction? Discover a handpicked selection of contemporary geometric abstract art and explore their visual language, hidden meanings and analogies.

ARTIST SPOTLIGHT

5 Surrealist Female Artists from Around the World

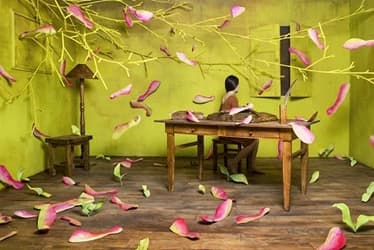

Surrealism painting is an amazing genre. It stormed the art world in the early 20th century, upending our notions of what could be painted and what the source of an artwork could be. Using the bizarre imagery from dreams, surrealists set the stage for a new force in all the visual arts — from painting to film, from literature to even music. The style revolutionized how we create. As with any groundbreaking movement, women made up a large portion of the best and most popular surrealist artists. Unfortunately, most people with a casual understanding of the field only know about Salvador Dali. Let’s set things right and celebrate some amazing women surrealists from around the world. Kay Sage Tomorrow is Never (1955) by Kay Sage The American Kay Sage’s (1898 to 1963) work falls on the dark side of the surrealist realm. Her pieces are brooding, desolate, and strange in the way that nightmare landscapes are strange. In other words, her work is incredible. Her paintings frequently make use of architectural motifs, often in a state of decay. She often used landscapes to define a large space, with dreary cloud cover to create an atmosphere of dread. While she was relatively well known during her lifetime, she never quite reached the heights that her work deserves. There is some renewal of interest in her today, and we hope that it continues. Her contribution to the surrealist movement should never be forgotten. Leonora Carrington The Giantess (1947) by Leonora Carrington Leonora Carrington (1917 to 2011) was born in the UK, though her later life in Mexico has made her legacy split by the Atlantic Ocean. Carrington was a prolific painter whose career marched on across seven decades. Over that time, her output included painting, sculpture, and writing. Many of her paintings draw from mythology, with an eerie starkness that brings a certain tinge of terror to her canvases. The contemporary art market has moved Carrington paintings for huge sums of money, like the $1.5 million price that The Giantess (pictured above) garnered in 2009. While in Mexico, she not only thrived as an artist but also as a political activist, helping to found the women’s liberation movement there in the 70s. JeeYoung Lee Love Seek (2014) by JeeYoung Lee JeeYoung Lee (born 1983) is an artist from South Korea. Her work is a contemporary play on surrealist imagery. Her process usually involves creating elaborate sets in her studio. She then photographs these dreamscapes, usually using herself as the model. Lee’s work is captivating and freeing to witness. The bizarre merges with the candy colored to create a trademark style. It’s also refreshing to see what artists can do by combining surrealism with photography. By bringing in reality through the camera, the effect of the strangeness is all the more poignant. While still fairly young, Lee has already achieved a high level of notoriety and exhibited internationally. Her name will no doubt continue to rise in the art world, as she has so much more time to produce great surrealist art. Portia Zvavahera Arising From the Unknown (2019) by Portia Zvavahera Portia Zvavahera (born 1985) was born in Harare, Zimbabwe, where she lives today. Her work takes some influence from her homeland, and her imagery is often taken from her dreams — a cornerstone of surrealism. Zvavahera’s brushwork and printmaking are brought together on canvases that express deeply human challenges, all while reveling in otherworldly settings. Her use of bold colors and striking composition wring out a great level of emotion in her work. Her paintings are widely celebrated around the world. She appears in international shows, in both solo and group exhibitions, and she has emerged as one of the most important contemporary voices in the art world. Remedios Varo Useless Science or the Alchemist (1955) by Remedios Varo Remedios Varo (1908 to 1963) was born in Spain, though her career took her across the world. She participated in the first wave of surrealism, helping to lay the groundwork for all the generations to come. While her painting is forward thinking in some respects, she took a great deal of influence from Renaissance art. Many of her paintings are highly allegorical, balanced in composition, and painted with many techniques borrowed from Renaissance masters. This gives her work a high level of continuity with the history of European art, despite her surrealist content. By the time of her death in the early 60s, Varo’s influence had spread far and wide. Her 1971 retrospective in Mexico City drew larger crowds than a similar event for Diego Rivera. That level of popularity is well deserved, as she left behind a stunning legacy of artwork. Passionate about Surrealism? Discover our curated collection of Surrealism paintings. This collection is perfect for art lovers who are looking to decorate their homes/offices.

ART 101

The Amazing Power of Color: How Artists Use Color In Art

We3’ve talked about the lasting appeal of black and white photography even discussed great painters who’ve turned to a black and white palette to create masterpieces. Now, it’s time to return to color. Because while there is certainly a place for monochromatic art, there is simply no denying the power of color. It is one of the most important tools in the artist’s toolkit. When we see rich colors in paintings, we have a surge of emotion, physical sensations, and a million little associations we’ve made with the color over our lives come rushing back. Getting Color Right Before learning how to use color in art, getting the color right is an important first step. For much of its history, Western art has tried to achieve realism through color, capturing it on the canvas through ever more advanced techniques. Nevertheless, there were still things artists could do with color to surprise and inform viewers. For instance, Dutch painter Johannes Vermeer (1632 – 1675) subtly used complementary and near-complementary colors to generate visualinterest (see above). And many, many artists would reach for certain colors for their symbolic meaning. Still, color was mostly limited to parodying real life. It wasn’t until the 19th century that things began to get more exciting for color. Monet Paints Light Study of a Figure Outdoors: Woman with a Parasol, facing left (1886) by Claude Monet Led by the likes of Claude Monet (1840 – 1926), the Impressionists tried to grasp how things actually looked in the moment. Monet in particular was fascinated by the way that time of day radically changed the true colors he was seeing. Monet was onto something, we now know that the visual cortex in the brain is capable of rapidly adjusting to light conditions, despite the actual color signals coming into the eye. He also used color theory extensively, making sure to bring complimentary colors together — pairs like purple and yellow, red and green, blue and orange. These colors set off each other, making both more intense. Still, this was all realistic in a sense. It was done to bring about a more human reality into painting. It would take a new wave of artists to go one step further. Matisse and Escaping Color Realism Woman with a Hat (1905) by Henri Matisse Henri Matisse (1869 – 1954) was an unparalleled forward thinker in art. Along with Picasso, he completely upended tradition’s centuries-long stranglehold on Western art. His experimental use of color is, to this day, his most long lasting achievement. He helped form Fauvism, a movement that broke the convention of using color realistically. Instead, he went for bright, bold colors — using them to create visual interest and aesthetic beauty, rather than strictly mimic reality. Fauvism only lasted a little over a decade, but the implications were enormous. They would go on to shake the foundations of the art world and help usher in modern art. Abstraction and Color No. 61(Rust and Blue) (1953) by Mark Rothko : Copyright Mark Rothko Fauvism pushed artists to be more creative and freer on their canvases than ever before, and later movements would use this new impulse to their full advantage. Abstract art moves away from representation entirely. In the early 20th century, artists began to experiment with this style. Some made less representational paintings of real objects, while others went off to paint entirely abstract compositions. And many cared deeply about color. Painters like Wassily Kandinsky (1866 – 1944) even worked through the spiritual importance of color, embedding his works with emotionally poignant hues. By the mid-century, Abstract Expressionists like Mark Rothko (Orange & Yellow Mark Rothko) (1903 – 1970) got rid of any pretense of a scene, building extremely simple compositions out of blocks of color. While controversial even to this day, his work studied the essence and character of colors, and examined how the simplest of contexts can change the underlying feeling. Since the Abstract Expressionists, contemporary art has gone on to continue where they left off. We are still seeing new approaches, new ideas, and new relationships between the artist and their palette. The history of art can never be understood without grasping that most fundamental of elements: color. Passionate about colors? Discover our curated art collection related to colors below. 1. Purple & Wine Artworks 2. Orange& Yellow Artworks Artworks exploring Cold Colors 3. Artworks exploring Cold Colors

ART INSIGHT

Famous Black and White Artworks

We’ve talked about the power of black and white photography in a previous article, now it is time to dive into great black and white artworks made without a camera. The following artists have created masterpieces using only two colors. We see in their work a heightened sense of composition and the ability to communicate just as much (if not more) with a limited palette. M.C. Escher Ascending and Descending (1960) by M.C. Escher Copyright M.C. Escher The Black & White artwork of M.C. Escher continues to delight us today, teasing our minds with fascinating, mathematically inspired pieces. His work playfully explores themes like tessellation, impossible objects, and the concept of infinity. Surprisingly, Escher wasn’t a mathematician by training. Instead, he absorbed the ideas as an artist, giving them life in the studio through an artistic, rather than a mathematical, process. His most popular works (like Hand with Reflecting Sphere [1935], Drawing Hands [1948], and Tower of Babel [1928] to name only a few) have gone on to be published extensively, making his work some of the most seen and beloved in our time. Kazimir Malevich, Black Square (1915) Black Square (1915) by Kazimir Malevich Malevich lived on the bleeding edge of the art world, both as an artist and critic. When he completed Black Square in 1915, he dragged the art world out into the avant garde with him. This achievement is simply a white background with a black square painted on it, a devastatingly simple composition. Hailed (and hated) at the time for bringing art back to the “zero point of painting,” it continues to be controversial to this day. Pablo Picasso, Guernica (1937) Guernica (1937) by Pablo Picasso Copyright Pablo Picasso Picasso’s massive masterpiece Guernica was painted to lament and commemorate the bombing of the eponymous city on April 26, 1937. It was during the Spanish Civil War, and the Basque town was bombed by both German Nazi and Italian Fascist forces to support the fascistcause there. To express the depths of sadness, Picasso eliminated color — a bold choice. But taking away color did not take away any of the painting’s power, in fact, the black & white artworks highlighted the severity of destruction and the despair of the event. Bridget Riley and Op Art Movement in Squares (1961) by Bridget Riley Copyright Bridget Riley Bridget Riley is one of the most accomplished names in Op Art — a style that creates visual art using optical illusions. While Riley has plenty of color work, her most popular pieces are often in black and white (like Movement in Squares [1961], pictured above). When you see these monochromatic patterns, the eye often is tricked into visualizing movement and even color. Robert Longo Longo has had a long and productive career in many mediums, but his black and white drawings — often working off of photographs — have made up his most important output. He reached prominence through his Men in the Cities series, depicting men and women in business attire caught in contorted poses. One cannot decide if these people are lost in a dance, being shot, or suffering convulsions. By sticking with black and white, the images have the sense of being objective, clinical. The series has gone on to be recognized as one of the most important of a generation. READ: How Artists use colors in their work. Jackson Pollock There might be no bigger name in abstract art than Jackson Pollock. His kinetic process of flinging paint onto canvases has ignited the delight and imagination of millions of art lovers. While he often used color, many of his compositions were purely in black and white (like the aptly named Black and White (Number 6) [1951]). These show all the forceful energy of his work, which is his calling card, while peeling away color. Franz Kline Painting Number 2 (1954) by Franz Kline Copyright Franz Kline One of the luminaries of mid-century abstract expressionism, Kline grew to popularity with only two colors: black and white. His striking compositions are now famous, with his style becoming iconic, even beyond the name of the painter himself. The story goes that Kline landed on his style because of some friendly advice from fellow artist Willem de Kooning, who told him to break a creative lull by drawing on his studio wall using a projector. That led Kline to pursue large, abstract art. Victor Vasarely Like Bridget Riley on this list, Victor Vasarely was a pioneer in the Op Art movement. And like RIley, his work often only uses black and white to achieve its effects. In pieces like Supernovae (1961), he is able to create dimensionality and movement without color, relying on small adjustments to a repeating grid to produce optical illusions in the human eye. Black and White Wall Art When we think of black and white, we almost always think in terms of fine art photography. But this list, far from complete, shows just how much other visual artists have been able to accomplish when they bring things back to these two fundamental forces of light and dark. Discover our curated collection of Black & White Artworks today.

ART 101

Why Black and White Photography Is Still Popular Today

Technology changes the way we make art. It always has, always will. As new pigments have become available, painters begin to use those new colors see our article on purple for a great example Photography, more than perhaps any other medium, is connected to progress in the underlying technology. After all, it wasn’t even possible to photograph anything until 1822, when the first photoetching was achieved. Since that time, new innovations created the ability for people to photograph on film, and it took about 100 years for that process to become fast and convenient enough for photographers to set out easily to take pictures. Even still, almost all of these photos were in black and white (also called monochrome), able only to capture the intensity of a light source. Even though color photography could technically be done by the mid 19th century, it was much more expensive and difficult. Through the 20th century, many of the technical limitations with color photography were overcome. Eventually, everyone with a few extra dollars could be a color photographer. For journalists and most at-home family documentarians, color was embraced as soon as it was feasible. But what do we see in fine art photography? The persistence of black and white photography themes. What was once a technical necessity, a choice forced on the photographer by the realities of their medium, is now a choice. And photographers continue to make the choice to shoot in black and white, and in large numbers. Let’s examine why artists still work in this style, and what we as art lovers gain from that decision. Taking Focus Probably the most persistent reason that photographers choose black and white over color is the way it changes their perspective and allows them to focus on fewer elements. Without color, compositions take on new dimensions. Darkness versus light becomes the central way that these photographs achieve texture and form. It’s that classic line that you hear for advice in any creative field: limitations are good for discovery. By taking color away, photographers can focus on fewer elements, leading to surprising images that wouldn’t land with the same force if color was involved. What that means is that photographers open up their work to a much wider range of subjects. By simplifying what they can present, they can actually present more. The Classic Feel Nostalgia is important, and that’s why the connotations around black and white photography are so powerful. When we take black and white photographs, we aren’t just capturing an image, we are creating a work of art. These photographs carry with them more than the scene they present, they carry an aesthetic that means something in and of itself. Black and white photographs appear serious, serene, and timeless. It can lend even the most contemporary scene (like someone scrolling on their smartphone) the air of all that fine art photography that came before. It is a visual bridge, lending heft and gravitas to the subject matter. That alone can be an interesting choice. By recontextualizing moments with black and white, we can hold them up and analyze them as crucial parts of the human condition. Go Toward the Light As we mentioned, black and white photography limits the elements you can focus on. The most crucial element of that is light. And nothing quite captures light in as pure a way as black and white photography. Without color, our eyes can easily make sense of how light is interacting with the world. Often, color adds in detail that actually obscures what light is doing. You have to have a well trained eye to see how light is actually bouncing around a scene when it is in full color. But black and white photography simplifies this, allowing the viewer to see effortlessly the living reality of light. That single feature of black and white photography has given us some of our most cherished images of the last century, and it will no doubt create more as we move into the future. The Future of Black and White Photography We live in an era where everyone has a smartphone capable of taking a seemingly infinite amount of photos instantly. They can be full color or black and white, and you can switch between with a tap of the screen. They can be morphed, adjusted, and augmented instantaneously — no more long hours in the dark room. What we see is that, despite these options, people are still drawn to the simplicity and narrative power of black and white. With so many options, people are still compelled to reach for this classic look. It seems that no matter what technological progress we make, black and white photography is here to stay. While it was created by accident out of the technical limits of a certain time, it has proven to be an important artform all its own. Passionate about Black & White photography themes? Discover timeless Black & White Artworks on RtistiQ.

ART INSIGHT

On “Orange and Yellow” (1956), by Mark Rothko

As the painter Mark Rothko used orange and yellow in his mature work, our artists today continue to use these warm colors moving the viewer’s perception of a luminescence to a place of mystical insight. It is through such bold color interactions that the spiritual essence of our contemporary artists is revealed. The result, for the viewer, can be an unbounded sense of awareness-even a kind of theology presenting itself... Rothko was insistent that his art was filled with content and brimming with love ideas. Still, he tried to remove all evidence of himself in the creative process. The layering of many thin washes helped to give his paintings a lightness and brightness as if they are glowing from within. In both instances the inner life of the painter opens itself up to alchemical magic and a mystery of theological proportions. Then, one is opened to the existential questions at the base of the human condition. It is here that Rothko’s sleight of hand brings the viewer closer to their own inherent desires for a benevolent meaning behind the things of this world. The ultimate aesthetic journey is offered to us through the possibility of the intricacies of Rothko’s color. Here we experience how art helps us as a balm, a salve onto the flesh of our souls. When tracing the mature work of Mark Rothko, back to the beginnings of his first imagery, one is able to uncover a truly seminal surrealistic vocabulary. The buried bodies of mythological creatures, stacked and organized in mystical tomb-like organization have alway fascinated lovers of Abstract Expressionism. Jackson Pollock’s, surrealistic imagery of human creatures, seem to me to have piggy-backed their way into modern art by way of the early ‘buried’ figures of Rothko. It has been written that these buried stacks of mythical bodies represent dying and dead ancestors in the artist’s family. A post-WWII consideration of such a spiritual journey by members of Rothko’s kin reveal the concrete tribulations experienced by the artist and the always threatening and gaping existential maw in the life of such a devoutly serious artist. From my own contemplation of Rothko’s “Orange and Yellow”, I think of the continual paradox in science that theoretically pulses me into the hearsay world of quantum mechanics. We “blink into and out of existence” say the scientists when contemplating matters of meta-reality—time and space. In his own way Rothko was affirming, in his most momentous works, the same metaphysical paradoxes of our greatest scientists. Both as sanctuary and quiet disruption, the art of Rothko teaches the art lover to travel in humanity’s psychological states. As we age in our search for our greatest humanity, death and transcendence simply resolve into an Inevitability we have always sensed might be true. “The people who weep before my pictures are having the same religious experience I had when I painted them,” said the artist. An intellectual among the painters of his time, he was well versed in the Greek Tragedies, especially Aeschylus, and later in Shakespeare. Nietzsche’s The Birth of Tragedy was an early and important influence. In his art, Rothko both affirms religious reality and takes it away. As one Anglican vicar told the Times of London a few years ago when the Tate Modern mounted an exhibition of Rothko’s late work, “For me the paintings are the tablets of stone of Mount Sinai, but with the commandments lost. They are icons of the absence of God.” Rothko would speak of the subject matter of his paintings as “the human drama”, especially that part of the drama involving death. All art, he said, “deals with the intimations of mortality.” We can certainly see this in “Orange and Yellow.” Still, in spite of the threat of death, all art dissolves in the immensity of a truly benevolent spirit. Inspired by Mark Rothko? Discover our curated collection of artworks that incorporates Orange and Yellow. Experience the illusion of these warm colors emanating light from within.

ART AND TECHNOLOGY

What is Certificate of Authenticity and why it matters for Art?

The art market has many traditions and ways that people do things that might not easy to grasp if you are just getting into it. Two of the most important are the certificate of authenticity and provenance. These two factors are extremely important to the price of an artwork and the buyer's ability to resell later at the same (or, hopefully, higher) value. These two concepts are essential oar on oneand for anyone going to navigate the art market, yet many people aren’t sure what they are. And even if they know what these concepts are, they still might not understand why they are so important. In the article below, we’ll explain exactly what these two terms mean and why they are important to the art market — and why you should take them seriously when buying art yourself. What is a Certificate of Authenticity? A certificate of authenticity is a document that offers proof of proper attribution to the Artist who created the artwork. It has typically been a piece of paper with the information on the artwork and its unique attributes, the Artists details, and signed by the Artist or a competent authority who has apprised the work before. When you buy a work of art, a certificate of authenticity is almost always provided. If not, be sure to ask for one. This little slip of paper might not seem like much, but it can mean the difference between having a work of art that nobody trusts is originally attributed to the artist, and one that offers you the right value when you resell. Without a valid certificate, it becomes hard for the art market to easily identify the creators details. If a fraudulent painting is convincing enough, most experts won’t be able to tell which painting is an original and which is a replica. That can be dangerous for the art market, because it relies on the unique value of the original for much of its price tags. Similar to artwork the certificate also can be easily copied or recreated, one of the reasons why in recent years sellers have begun to add holograms and other difficult to duplicate features to their certificates and linking back to their original. With a certificate of authenticity, you have a vital piece of evidence that the painting you own is the real deal, not a forgery. That leads us to our next term. What is the Provenance of an Artwork? As with so much nomenclature in the artworld, provenance is a word that comes from French. Provenir means “to come from,” and that’s exactly what it means. Provenance shows the history of people and institutions that have owned a work of art throught its life term. The evidence that makes up the provenance of a work can be varied. Provenance can be made up using: Certificate of authenticity Receipt from the artist Receipt from the original gallery sale Auction records and sale reciepts Restoration details and reciepts Appraisal from an expert in the era When you want to preserve the provenance of an artwork you buy, always give preference to the written word. Someone just telling you that a painting is the real deal is not enough to prove that it is a genuine original created by the Artist of interest. The provenance of some artworks is better established than others, and it’s always a good thing to factor in when you are purchasing a work of art. You don’t want to pay the price of an original only to later find you have a forgery. Why do These Matter? As we can see, certificates of authenticity are closely linked to provenance. Those certificates often make up a good deal of an artwork’s provenance. Together, they speak to one of the most important features of a work on the art market: originality. But why is originality so important? The art market has a difficult job. It has to figure out a way to price and move pieces that have a highly subjective value. But one of the main ways that people have agreed to value art is on originality. Sure, part of that originality is in how original the ideas or techniques being employed are. But a more important form of originality is in the object itself: is this the original or is it a copy? But establishing if something is a copy can be hard. As we mentioned earlier, a really good forger can even trick the experts. And if you also have good forgeries of documents to establish provenance, then you have a big problem on your hands. In general, provenance and certificates of authenticity are ways that offer some level of protection from purchasing a forgery. By understanding them, you have a much better chance of getting valuable work for yourself that might turn out to be a good investment one day. Read our quick guide on how to secure your art in today’s digital economy.

ART MARKET

The History of Pink: from Pompadour Rose to Millennial Pink

Believe it or not, Millennial pink is a color. Still hard to pinpoint the exact shade of pink, it is sometimes described as "dusty pink", "quartz pink" or "peach pink". Clear thing is that it has become the statement color of a generation. Since being announced as PANTONE color of the year in 2016, this pastel color has grown to become one of the most loved shades in fashion, design, or art. If for Gen Z (Millennials) pink is hip, strong, and androgynous, if you think about but the recent appropriation by feminists around the world as a powerful, socio-political mark, through the “pussyhats”, this pastel color has a long history of shifts in cultural significance and symbolistic. Pompadour Rose In the West, pink first became fashionable in the mid 18th century, when European aristocrats, men and women equally, wore powdery color garments as a symbol of luxury and social class. Madame de Pompadour, the official mistress of Louis XV, loved the color so much that, in 1757, French porcelain manufacturer Sèvres had to create a line of porcelain decorated with an exquisite new shade of pink and named it after her, Rose Pompadour. A Sèvres 'Rose Pompadour'-ground vase and stand circa 1758 Madame de Pompadour (1759) by François Boucher Mass-produced Pink For the following century, Pink continued to be worn by both men and women, as well by children regardless of gender. The meaning of pink took a turn inl the mid 19th century when the feminization of pink begun. Pink became an expression of delicacy at the same time with men in the Western world transitioning towards wearing mostly dark, sober colors. At around the same time, Pink developed the first erotic connotation, suggesting the color of flushed skin. Lingerie in shades of pink became increasingly common. The industrial revolution making the mass-produced goods widely available meant a shift from sophistication to vulgar. Pink went from luxury to working-class. As seen in the interior depicted by post-impressionist artists at the beginning of teh 20th century, the color pink was well adopted by the mainstream. A pink corset from the 1880s credit: FIT Museum La Chambre Rose (The Pink Bedroom) 1910, Edouard Vuillard The Pink Studio During the 20th century pink’s cultural significance underwent further shifts, especially in art. Its exotic appearance made it a perfect choice for Matisse and other fauvists who were refusing to accept that color must reflect the real world, as seen in his painting The Pink Studio which in reality had no pink walls. The Pink Studio (1911), Henri Matisse Gentlemen Prefer Blondes in Pink In the male-dominated world of Dadaists, Surrealism and American Abstract Expressionism, pink was of no interest for artists. The same attitude towards this color was reflected by the wider society. By the 1950s, pink had become more gender-coded than ever, thanks to postwar advertising, especially in America. Pink was used as a symbol of hyper-femininity and gender-based roles in society, creating the stereotype: "pink for girls, blue for boys". Merlyn Monroe, the embodiment of the the 1950s idea of femininity, soft-spoken, erotic but short-lived, as a flower, is often remembered for her pink gown from the movie Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1953). Pink goes Pop By the 1960s, pink was flourishing within pop culture. The dresses were pink, the bathrooms were bubblegum pink. Even the most tragic event of the decade, the assassination of JFK, had a touch of pink. On that day the first lady Jackie Kennedy, a fashion icon, was wearing a raspberry pink suit designed by Chanel. As a translation of mainstream culture into high art, pink found its way back into art through Pop Art. Through the art of Andy Warhol, David Hockney and even minimalist artists, such as Dan Flavin pink resurged in art during the 60s’. Pinkout of a Corner (1963), Dan Flavin MarilynMonroe (1967), Andy Warhol Pink with a Punk Attitude Over the past decades, the degree of association between femininity and pink has both grown and shrunk. In the ’80s the gender identification through color was made from birth, in the ‘90s and early 2000s, toy-store aisles that featured toys for girls became exclusively pink. But a the same time, pink was reclaimed by gay rights activists since the ‘70s. Furthermore, since the rise to the cultural dominance of girl bands (Spice Girls) and female punk-rock leading figures (Gwen Stefani’s fuchsia pink hair) in the ’90s and 2000s, pink has been reclaimed as a symbol of feminine power and strength. Restaurant designed in 2014 by India Mahdavi Pink and the Millennials Once a color statement for all things feminine, pink is now widely accepted as an almost gender-neutral color, due to the popularity of Millennial Pink, a dusty, subtle shade, which became ubiquitous in the 2010s. Used in fashion, design, architecture, and art, it became the go-to color for a generation willing to accept differences and embrace weaknesses. The Millenials that grew up with social media and instantaneous exchange of information are whilling to openly speak about formally considered taboo subjects, such as mental health or gender identity. Their approch to life is softer, as a toned-down shade of pink. Their addoption of pink (Millennial Pink) came as a reaction against the stereotypes associated with pink. View from Wes Anderson’s cult movie The Grand Hotel Budapest (2014) Having said all this, let’s not forget that the meaning of any color is a cultural construct, it’s the society that is giving meaning to colors. As the years will pass by, the meaning of Pink might shift again and again. If I got your attention and we sparked your interest in Pink, check our curated collection of contemporary art: Millennial Pink and Other Pastels. Author: Floarea Baenziger

INTERVIEWS

Get to Know Dan Arcus - A Q&A with RtistiQ

Dan Arcus in his studio Dan Arcus is a Brussels-based contemporary artist. Having studied in Cluj, Romania, he draws inspiration not only from cinema and books but as well from news and social media. In his elaborate compositions he often depicts historical subjects taking part in imaginary scenes. His work invites the viewer to question reality. 1. Where do you live right now? I live in an apartment in Brussels, Belgium, and my studio is downstairs. 2. Where do you look for inspiration? My inspiration comes from a great variety of sources: cinema and books, television but also news, social media, and online archives. My concepts are generated by processing all the information I access. Very often it comes as a subtle irony or prediction of the outcomes of the ridiculous, the absurd, the ignorance, and the arrogance of our society. DAN ARCUS, Figure Study AV 3. How do you see the role of figuration in contemporary art? Since the "liberation" of the art market facilitated by the online, many of the aesthetic or conceptual codes have been adjusted to a more inclusive selection of artists, more accessible to the general public, and less interested in the complexity of the artistic process or pretentious conceptual explorations. For any market, the role of the public is essential. Most people receive an aesthetic education from nature, quotidian images, cinema, television, and maybe a brief encounter with very famous old masters during school years. Therefore, the emotional impact of an artwork depends, in many cases, on the viewers’ ability to interpret an image through the familiar aesthetic codes that they are familiar with. “Figuration” in contemporary art takes many forms and develops on different levels of accurate representation of the surrounding reality, hence the ability to provoke an emotional response, a debate, or a review, through content that is familiar to a larger part of society. Due to this principle, a higher interest in figurative art is generated, therefore a higher demand for it. On the other hand, the same wide market continues to appreciate and choose abstract art for its decorative role of an interior and for the neutrality of the conceptual or symbolic interpretations of that image. In many cases, abstract art becomes the "safe" choice. Figurative art facilitates the communication of philosophical ideas, making them accessible to a large part of society, and can be a very powerful tool for information dissemination. The role of figuration in contemporary art is not very different from what it used to be in the past. It continues to inform, educate, stimulate emotions, and to question. It also generates technological development and the exploration of artistic processes or the science behind them. It remains essential in the basic training of any professional artist. DAN ARCUS, Ritualic gestures I, II and V 4. How would you describe the relationship between art and society? Is society reflected in art? First of all, art is for society! In any shape, art is made for people and its ultimate purpose should be considered in relation to society. (I exclude the artistic manifestations of other species since I don't think it is relevant here). Last year has brought to the public’s attention the concept of "essential occupations". When the majority declares art as unessential and easy to discard in case of an ultimate survival test for humanity, they ignore the fact that artists are part of the creation of almost everything man-made. Can anyone imagine a society without music, literature, cinema, television, fashion, design, architecture, etc?! Can anyone imagine how the screen of a smartphone would look without the design team to shape the product, the user interface, and so on? How about surviving through the pandemic without Netflix? :P Joke aside, probably no species need art to survive, but humanity does! So art and society are so strongly intertwined that separating one from another would be like separating the structure of a building from the building itself. The building would collapse and the structure, even if it still stands, would lose its purpose. DAN ARCUS, The Evaluators, detail 5. How do you choose the topics of your artistic explorations? My artistic exploration develops in two directions - the psychological impact of the image and the technical means to achieve an emotional response. The topics I choose are usually related to my perception of contemporary society and the increasingly finer line between what reality is and what we are told it is. We are experiencing in recent years unprecedented uncertainty over what is real and what is fabricated and ultimately what is good or wrong. Many of us feel the need to escape the pressure, to navigate and discern through the jungle of information. The topics I choose are either related to observing the society’s reaction to this phenomenon or create a refuge in an alternate reality with possible metaphorical interpretations that would invite contemplation or meditation. 6. How relevant is your heritage for your art? I cannot determine precisely how much my Romanian heritage has influenced my artistic production or if it plays an essential role. Of course, much of who I am today was formed during the years I grew up, through the education I received in Romania. I probably include unconsciously in the artistic process aspects of my culture but in my work, I’m not determined by any cultural, ethnic, or geographical boundaries. I like to believe that I am first a citizen of planet Earth, then of Europe, and only then of Romania and Belgium. So my cultural heritage is probably as important as this order suggests. DAN ARCUS Fish Tank 7. What is your main medium? Are you looking to explore other media in the future? I work mainly in oil and pastel but I do a lot of experimentation with inks, pencils, acrylics, etc. I am enhancing my digital skills in order to develop relevant media. I am as well flirting with 3D software so I could explore 3D printing and sculpture. 8. Any thoughts on social media and art? Social media is a reality. Whether some dispute it and others embrace it, everybody should agree that it is a powerful tool of information dissemination. That being said, I cannot think of a better contemporary channel for increasing visibility for art. 9. What else we should know about you? Even though I am not that much in touch with the fashion world anymore, from time to time I like to take on different projects that give me a reason to put myself up to date with the latest pulse of this domain, and of course, it is always very nice to see people wearing something I’ve created. Discover more art by Dan Arcus by checking his profile on RtistiQ.